100 Years Ago in History: “I can not yield any further.”

February 17, 2022

Black History Month Presents: An early fight for Civil Rights by Putnam County’s Hamilton Fish.

As if a mirror to today’s divisiveness, 100 years ago New York Republican Representative, Congressman Hamilton Fish, repeatedly refused to yield as he took to the House floor to advocate for anti-lynching legislation to assure all people within the jurisdiction of the United States the equal protection of the laws and to punish the unconscionable crime of lynching. It was February, just days shy of President Lincoln’s birthday, and a precursor to today’s Black History Month.

In 1922, The Dyer Bill was written and re-written since 1918 to help stop violence from race riots and prevent lynching which was predominantly taking place across the South. Although the bill was far from finished, Fish fueled the flame of change.

By January 1922, the bill was passed by the House of Representatives and put to the Senate floor for a vote. Unfortunately, a filibuster by Southern Democrats put its passage to a halt. Fish took to the floor and was reported in the columns of The Brewster Standard as being “generously applauded and highly complimented” for the opposing stand he repeatedly took that day against states that failed to convict and jail offenders.

“I believe that Abraham Lincoln would turn in his grave if he thought that 60 years after the emancipation proclamation a Republican House would hesitate to pass legislation,” said Fish, according to extracts from the Congressional Record. “The spirit of Abraham Lincoln still lives and the Federal Government is obliged to take cognizance of the hideous plague of lynching and provide a penalty so drastic as to render it dangerous for future mobs to indulge in.”

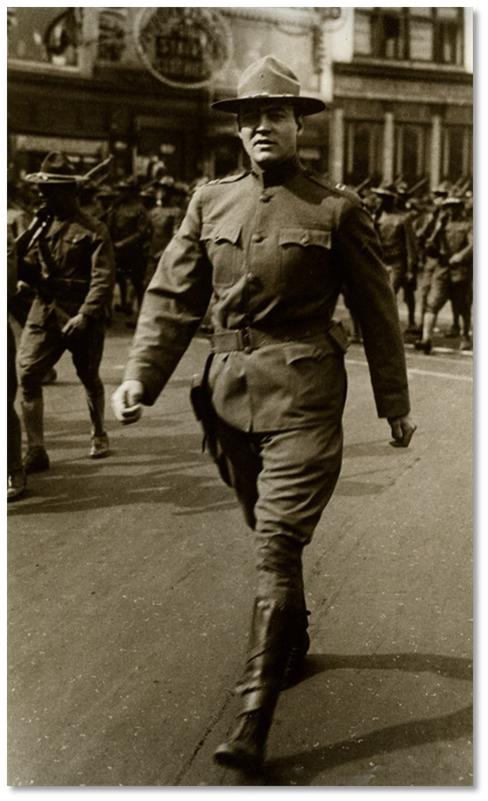

Fish had much experience witnessing the racism that soldiers of color endured in World War I, and advocated for the rights of Black American veterans. His dedication to the 15th Infantry, later known as the 369th Harlem Hellfighters, whom he commanded in France, may have resulted from the fact that some of his men made the supreme sacrifice, laying down their lives to make the world safe for democracy.

According to Fish, each one of his men went into the war feeling that he was, “fighting not only to make the world safe for democracy but also to make this country safe for his own race.” Fish went on to commend the loyalty and bravery of the soldiers of the 369th.

On that day, Fish called out to the floor that the legality of this bill would take a long time to be ironed out due to constitutional issues and arguments. However, he stood his ground stating, “I can not yield any further,” when it came to humanity. He continued, “I have sworn to support the Constitution of the United States and on that account, if for no other reason, it would be my sacred duty as a Member of the House of Representatives to vote for a drastic anti-lynching bill to protect the rights and lives of American citizens everywhere in the United States and put an end to lawlessness which threatens the administration of justice.”

One hundred years ago, Hamilton Fish recognized the fact that the bill would not necessarily solve the issues of race, but he knew it was a step in the right direction.

Ellie Cassidy is currently working on her Gold Award relating to the history of the 369th.