Summing Up Your Life in Six Hundred and Fifty Words or Less

September 26, 2017

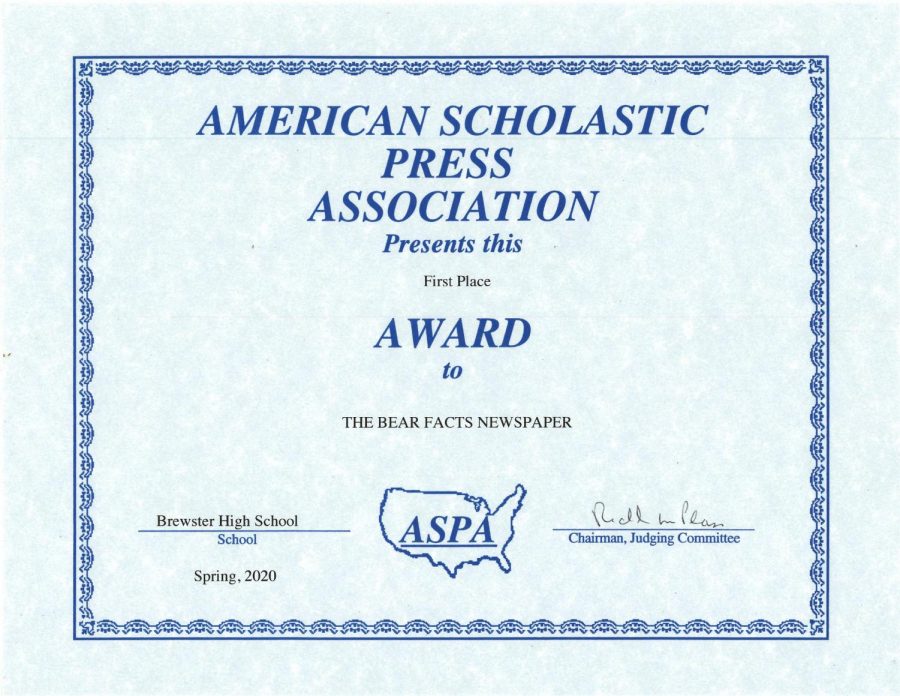

The fall usually means one thing for seniors: the college essay. The weight of the college essay lies heavily on the shoulders of many students as they attempt to reveal their character to college admissions boards, hoping to get that stamp of college acceptance. While this difficult task is being undertaken, some students tend to take it as an opportunity to shine as writers and reveal their best selves. The editorial staff of Bear Facts would like to take the opportunity to highlight some of the great work that our students are accomplishing.

McKenzie Quinn

I have to tell her.

When my mom came home from her latest trip to Trinidad, I was expecting updates on my grandmother’s mango tree and the family friends who always seem to drop everything to spend time with us. Instead, my mom sat me down and began to unpack every detail of her spontaneous visit with a Hindu Pundit.

With just my name and date of birth to guide him, the Pundit proclaimed that my wisdom extends beyond my lifetime and that I have the ability to see things for what they truly are. Listening to my mom recite this information made me smile. I could see the faith in her eyes as she held onto that vague description as though it were the perfect synopsis of her daughter’s story. Yet, the tilt of her lips faded as she continued to recount the meeting.

Clouding over my perceptiveness was a dark energy, which as the Pundit explained, manifests from the alignment on my planets, revealed to him by the study of Vedic Astrology. The existence of said negativity is referred to as a graha, which was going to be with me for a year.

Before I could even get a word in, a small bottle of what looked like blood (which I later learned was blessed oil) and a necklace with a pendant that resembled a bullet, was placed on the table between us. I was instructed to wear the necklace—which stored blessed herbs—every single day and apply the oil to my hair each morning.

My initial reaction was jokingly to ask, “Am I going to die?” I was never the kid to jump over cracks in the pavement or pick up pennies. My behavior stems from logical thinking and the understanding of probable outcomes. By complying with the Pundit’s advice, I would contradict everything I’ve come to know. So, I simply refused.

For days on end my mom asked. And begged. And looked at me as if my apathy was destroying her. Eventually, I removed the necklace from her jewelry case and clasped it around my neck, not because I wanted to escape impending suffering, but because it was important to my mom. Seeing my mom at ease was a good enough reason to do just about anything, no matter how far it went against my personal ideologies.

And even if I wouldn’t admit it out loud, I began to love the way the necklace looked on my chest. It seemed to match with every outfit.

Each morning at 6:45, I knew to stand in front of my mom’s bathroom sink. That was the time when she would take out the bottle of amber liquid and work a small amount into my scalp. I became accustomed to our routine. It gave us a moment to pause and connect amidst the chaos of rushed makeup and wrinkled shirts.

I didn’t even mind the occasional fasting, or the weird looks I got after explaining to my classmates that no, I wasn’t wearing ammunition around my neck, but rather a layer of spiritual protection.

I felt like I was finally able to do something for my mom that was more than a homemade card or surprise birthday party. My graha mattered.

That’s why I was on the verge of tears as I approached my mom. But, I had to tell her. My fists clenched as I held onto the chain, the distinct pendant lost among blades of grass.

It took minutes for my mom to forgive me, and days for me to forgive myself. Since then, no ill fate has been bestowed upon me, which hasn’t come as a surprise. Other necklaces have worked their way into my wardrobe, ones that earn a lot less attention. Yet, my graha hasn’t restricted me, it’s expanded my perspective. I’ve seen why faith is not only reasonable, but a fundamental aspect of humanity.

Valerie Mituzas

I’ll never be able to tell anyone where I get my laugh from, my eye color, my passions. I’ll never be able to determine who I resemble, of the people around me. I’ll never grow up and be as punctual as my mom or as extroverted as my dad. Despite my sister and I sharing a similar Russian background, we’ll never share resembling interests. I’ve also never been able to experience the feeling of knowing that I am who I am because of my mother or my father, and I never will. Ideally, if I had to think of a million other “side effects” of being adopted, I could.

Growing up not having parents and family members to hold accountable for my inherited characteristics has allowed me to live a very unconfined and self-contained life. Especially, while being someone who is conspicuously incognizant about their identity, I’ll always be someone who wants to distinguish more about who I’m supposed to be.

All my life, I have been aware of my autodidacticism. Since the age of two, I’ve been drawn to art and music. I’ve taught myself how to play the piano, guitar, cello and ukulele. I’ve taught myself how to speak French, write in script and how to play chords to songs in my dreams. I’ve never asked anyone to teach me these skills, I didn’t need to. If I’ve ever wanted to learn how to do something, I’ve always been inclined to make it happen on my own.

Throughout school, most of my peers assumed they knew what they were supposed to grow up to be, based on a “guideline” their parents had left for them to follow. I remember all the times my friends would ask what my parents did for a living and expect me to say I aspired to do the same. Even as I matured, that never seemed to be the case. Eventually, everyone has to grasp an understanding of how to build upon their passed down traits and characteristics in order to become someone. By not having those distinctly passed down to me from my adoptive parents, it’s as if I’ve been exempt of having limits and expectations for who I want to be.

I know I won’t ever have to follow in someone else’s footsteps. I’ve been creating my own. I’ll consistently want to break away from people’s assumptions and expectations of who I’m alleged to be. The easiest way for me to do that is through art. When I’m eye to eye with a canvas, an instrument, even a blank sheet of printer paper, every doubt, every fear and every problem vanishes. Even as a child, I knew there was that same promise of tranquility every time I emptied my mind through art. But, with happiness comes imperfection. With every mistaken brush stroke, every doubtful melody and every crumpled piece of paper, I know I’m one step closer to my limitless goal of becoming someone.

I’ve always felt the same undeniable confidence when it came to who I want to be, despite my age or differences among my family and friends. I know when I’m living on my own, alone with my canvases and sheet music, I won’t be worrying about who to be. I’ve known since the moment I opened my eyes. I’ve been who I’m supposed to be, who I should be and who I want to be. As I experience the intimidating world of adulthood, becoming someone will already be checked off my endless to-do list. I’ll already be the person I’d do anything to become. That someone is me.

Feyisetan Falana

I have a hat. Actually, I have three hats. And there may be more that I haven’t yet discovered.

Throughout my life, I’ve been rotating these three different hats. The white hat. The black hat. The hat with the little label in the back that says ‘Made In USA’. I’ve worn each distinct hat in each place that I call home.

Back in my hometown of the Bronx, the first hat I wore was the white hat. I remember that particular day back in my large third grade classroom. I was a typical, curious eight-year old girl. The only difference was that I didn’t use the “Bronx slang” like my classmates. One of my classmates asked me, “Why do you talk like you’re white?” I was extremely puzzled by her question. Did I really sound white? What was “talking white”? This brought a great deal of distress upon me as I started to notice many traits about myself that related to my classmate’s question. I started to question the way I talked, the way I acted and even the way I spelled my name. Who was I? In third grade, I came to understand my first hat. The white one.

In seventh grade, with my white hat, I moved upstate to Brewster, NY. Moving to suburban Brewster would provide a fresh start. I was interested in trying on a new hat. I made new friends, met new teachers and adapted to my current school. I was hoping that I wouldn’t be limited to just one hat, but one day, there it was. The black hat waited for me while I quietly waited on the lunch line. An unfamiliar boy approached me. He said, “Aren’t you supposed to be ghetto since you are from the Bronx?” I looked at him for some time. I was shocked to be asked this question on the fifth day at my brand new school. I thought that things were supposed to be different around here. I thought I could actually be just me, without having to wear a hat at all. Especially, a new hat. The black one.

A few years later, I traveled to Nigeria to visit my relatives abroad. I was so excited to experience my native culture in the motherland. I could sense a strong feeling of belonging with my people, people who related to me and shared a deeper understanding of my identity. In Lagos, I came upon a little street vendor with some cultural jewelery. I asked, “How much is the necklace with the red beaded flowers?” I spoke with my American accent, so I sounded like a foreigner. The vendor responded in his heavy Yoruba accent, “This costs 1000 Naira.” My mom replied in Yoruba to the salesman, “What’s the real price?” This guy was shocked. He thought that my family consisted only of English-speaking tourists. My mom negotiated the price of the necklace down to 500 Naira.

As we drove to our next destination, I thought about the effect this man’s behavior had on me. Did he actually inflate the price since I was American? Couldn’t he see that I shared his Nigerian blood? In addition to the necklace, I had received my third hat. The hat with the little label in the back that says ‘Made In USA’.

I still find myself juggling these hats as I move from the Bronx to Brewster and back to Nigeria. I was expected to wear one of these hats at all times, apparently.

But why must I let others decide which hat I wear? Why can’t people get to know the real me? The me who wears whichever hat she wants… or doesn’t wear one at all.

Erin Lennon

It’s 2007. I’m gripping the hand of my five-year-old brother with all my might. I’ve been lecturing him on the dangers of Halloween. Don’t eat anything already open. Don’t stand within reach of strange cars. Don’t leave my sight. We look up, and there he is. The Scream, in all of his glory, slowly approaching us. His black robes flutter ominously, and he’s moaning, like he’s in pain. Every time he takes a step forward, we take one back. Before long our dance reaches such a tempo that we’re sprinting up the hill behind us, our small arms pumping to keep time with our legs. I push Brendan in front of me and risk a glance backwards. My grandmother is holding a Scream mask, doubled over, tears of mirth streaking her wrinkled face. I scowl at her, pouting. And then I ask to try on the mask.

I’m in sixth grade, sitting with my brothers on the old couch in the new house that doesn’t quite smell like home yet. We’ve been left alone for the first time. I’ve gone around making sure all of the doors are locked, turning lights on and off so that if anyone drove by, they would assume that my parents were working in their home office. I’ve carefully screened the movie we are about to watch, ensuring that it is clear of profanity. Meanwhile, across town, my grandmother is instructing my older cousin. They will drive slowly down the road to our new house with the car lights off. She will park at the edge of the woods, and he will creep through our yard under the cover of darkness. Just as I’ve quit my pacing and hand wringing, they have arrived. As my brother hits play, I look to my left out the window. I expect to see my own reflection, but instead find the face of a man looking in at us. Needless to say, we scream. We dash upstairs, looking for a phone to call my parents, the cops, anyone. The front door bangs open, and I hear laughter. Curse her and her spare key. But I laugh, too.

My grandmother’s goal has always been to amuse others. She puts on a show for us; her antics have no boundaries, and nobody is safe from her pranks. I have always been her antithesis. My entire life, I have fought to be in control. I plot and plan and constantly rehearse scenarios in my head to make sure everything goes just as I need it to. Occasionally, something will disrupt my plans. Locking myself out of the house. Getting sick the week before an SAT. Leaving my wallet at home. Little things set me off and before I know it I’m checking my pulse and counting my breaths to keep myself from getting worked up. Nothing challenges my perfectly arranged existence like an afternoon with my grandmother.

Her form of acupuncture can’t be seen, but she still manages to hit every one of my nerves. And yet, nothing is quite as good at quelling my anxieties. My personal anti-hero, she allows me to see the world through her eyes when I need it most. While my views are usually clouded with worry, hers are decorated with simplicity. And somehow, the little things become little again.

I’m seventeen, standing at the top of the hill in the pouring rain. There’s lightning, but our counselors’ requests for us to stay inside our cabins have been ignored. I look out below me. There’s a tarp, some dish soap, and a lot of mud. I crack my knuckles and shake out my hands. I take three deep breaths; two fast, one slow. Close my eyes, and think of my grandmother. I slide.