Book banning has been making the headlines for the past couple of years. Maya Angelou, Toni Morrison, and Anne Frank are just some of the names on a continuously growing list of authors whose books have been banned. Yet, book banning is not a new concept and can be traced back in American history before our independence when we were just the British Colonies. An early example of book banning in America is when in 1650, the Puritans in the Massachusetts Bay Colony banned The Meritorious Price of Our Redemption by William Pynchon. His writings challenged some of the Puritans’ teachings and its ban and subsequent burning is the first recorded example of book banning in the United States. While this was only the beginning of banning books, it foreshadowed the conflicts that would arise in the future over literature that others deemed to be controversial.

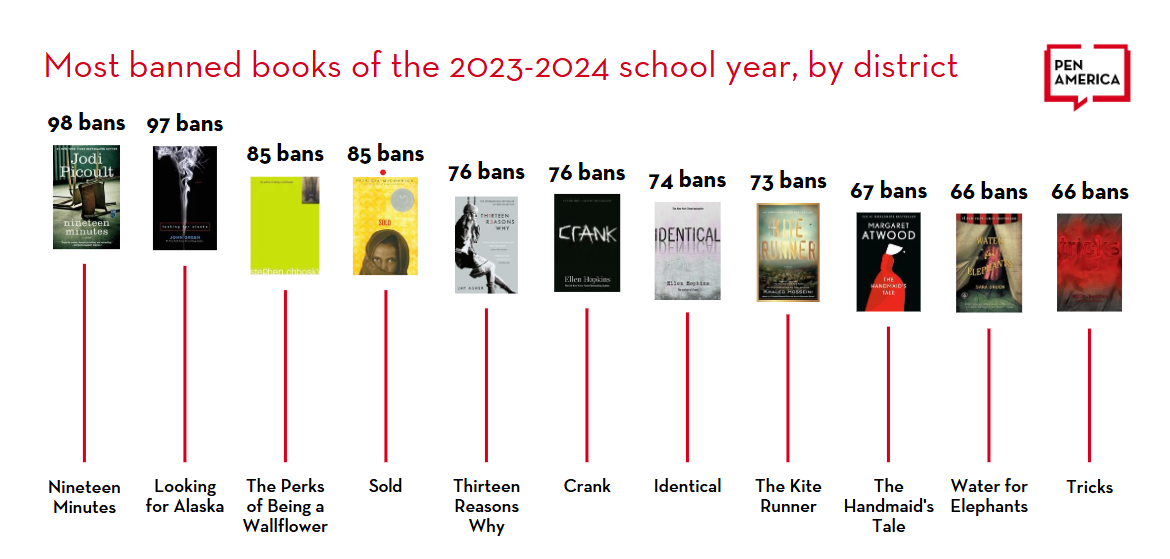

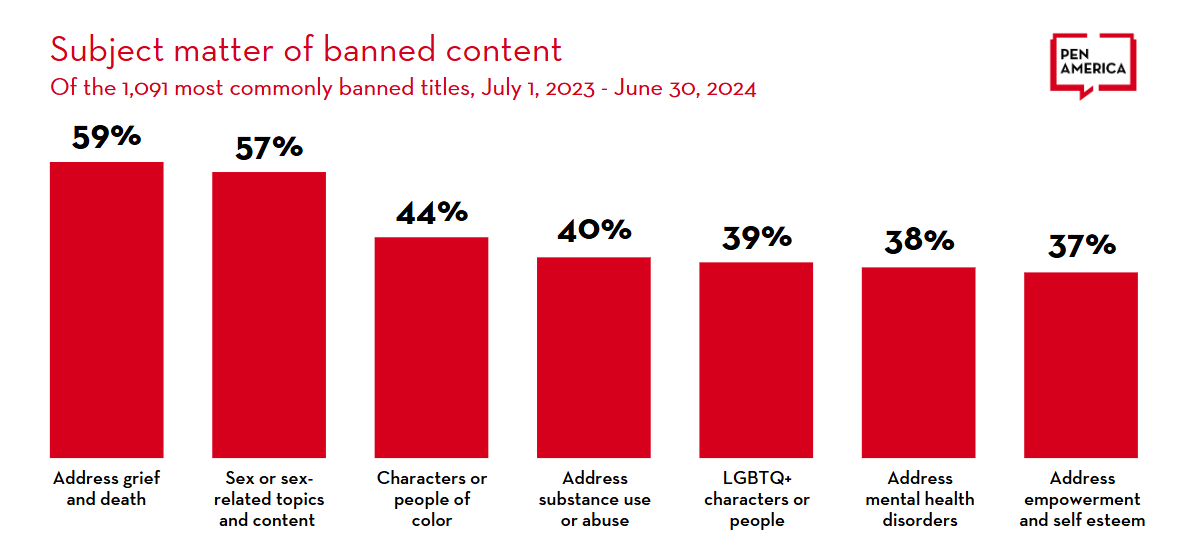

However, in more recent years, book banning is not something that we can sweep under the rug. It is becoming more and more prevalent across the nation. According to a report published by Pen America, more than 10,000 books have been banned from schools and libraries throughout the 2023-24 year. This is a significant increase from the 3,362 books the previous year. In these 10,046 instances, 44% included characters of color, while 39% included characters or references to the LGTBQIA+ community. Many of these books also depicted themes addressing mental health, grief, death, and substance abuse. The removal and censorship of these books affects the education of all students in a specific school and leads to an uphill battle for those on the side of education.

When books are banned, students lose an opportunity to explore ideas that may help them grow and shape their future. Limiting the points of view that students can read restricts their ability to analyze complex issues and think critically on topics they may not fully understand. Banning books teaches many students that there are topics that are too “dangerous” to discuss and learn about which discourages their curiosity and diminishes their chances of open and honest dialogues. The removal of books also impacts students’ knowledge and understanding of past historical events and awareness of those who came before them. Some commonly banned books include The Diary of Anne Frank and To Kill A Mockingbird, which provide crucial lessons on oppression and racism. The banning of these books removes the insight on these historical events and can lead to a lack of understanding of our past.

Students, though, are not the only people and communities that feel the impact of banned books. Banned books go beyond the books that are read in schools. They have traveled to the books that are carried in libraries. By banning books in public libraries, ideas and facts become marginalized. Books with different perspectives and ideas, have now become less accessible to those who may not be able to afford to purchase books. Libraries are a crucial resource for the public and banning books does not serve the community as public libraries should.

Many authors are also being impacted by book banning. They have had to face forms of “soft censorship” when teachers and libraries steer clear from banned books and self-censor the conversations they have for fear of real censorship. They are also facing a form of censorship that is rising in popularity named targeted weeding. Weeding out damaged and old books from a library’s shelves is a common practice. However, target weeding is when certain titles are removed from shelves based on the content or an ideological stance. It can be very difficult to monitor these tactics, but from what we have been able to track, there are multiple cases where dozens of books containing diverse themes such as racial inequality are being weeded out. So while authors not only have to fight against the fear and anxiety while creating their book that one day it may be banned for a feeble reason, they also have to push through forms of censorship that can be hard to track and fight against.

Book banning is not only a form of censorship against the author, it is also an infringement of the first amendment, which prohibits government actions that try to suppress viewpoints or content. But recent government decisions have intensified arguments over this line and have made the impact of free speech more and more prevalent. The first amendment safeguards an individual’s access to information and ideas. Yet, when local and state governments remove or restrict access to certain books from local schools and libraries, they are acting towards censorship. These actions limit readers’ exposure to different views.

Many local governments have stepped in when schools ban books using the reasoning of age-inappropriate material. In the case of Little vs. Llano County, a local library was ordered to return books to the shelves that were removed. The removal of these books, based solely on a disagreement of their viewpoints, was an infringement of the first amendment. This is not the only example of local schools and libraries being ordered to return books to the shelves. However, with the federal government stating in a 2025 decision that what is considered “age-appropriate” books falls under local jurisdiction, more and more local governments are removing books.

Now, it may seem that there is not much that we can do to fight censorship. But this is definitely not true. When people try to ban Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 (which discusses the detrimental effects of censorship), participate in your local library’s banned book week celebration. When George Orwell’s criticisms of authoritarian governments become debated, shop at your local bookstores that are making those books accessible.

While book banning, censorship, and first amendment infringement remain ever-growing issues, initiatives like these ensure that students, authors, and citizens have access to diverse content and ideas. Withholding information from the public is extremely damaging to education and critical thinking. Understanding viewpoints outside of our own is how we grow as a nation.