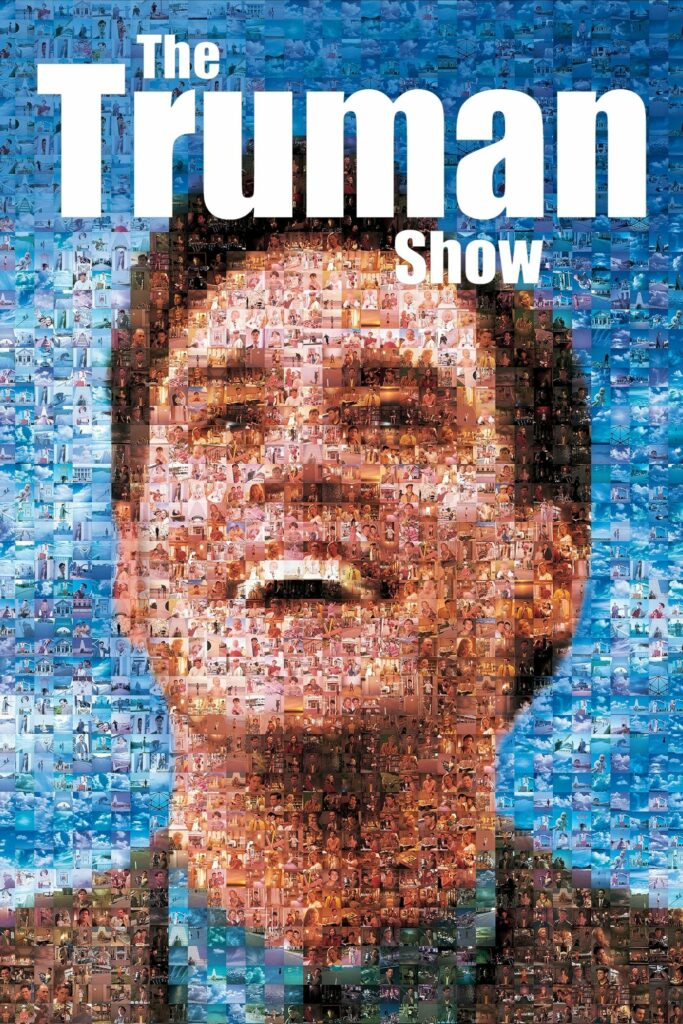

Throughout all of film, we look to define our reality. From the abstract work of experimental film to the blockbusters screened across theaters globally, each is an attempt to weave our varied interpretations of the world’s nature into visual storytelling. We often turn to film as an answer of unwavering certainty: in a world of unknowns, can’t our screen provide us with a simple solution? But film, like any other art form, should rather evoke a questioning, not provide an absolute answer to all. The complexity of the world cannot be answered within film, but it can be explored.

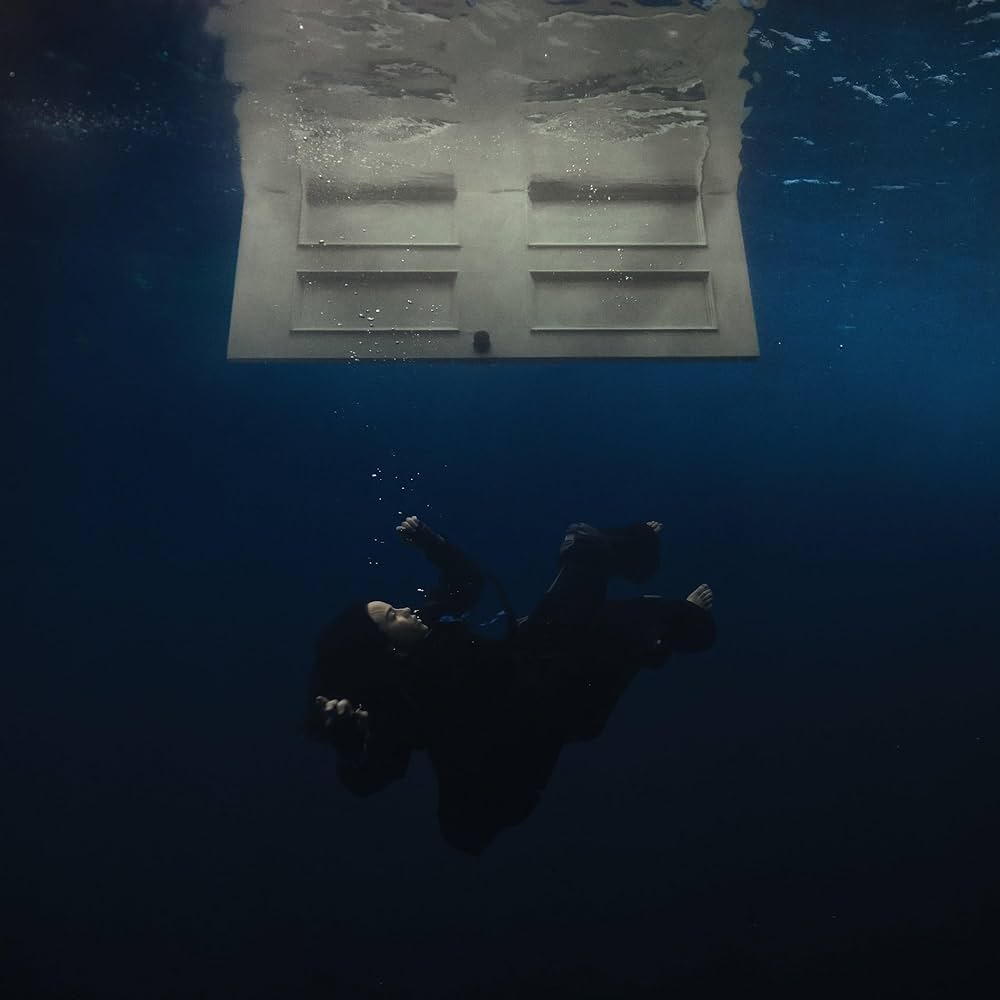

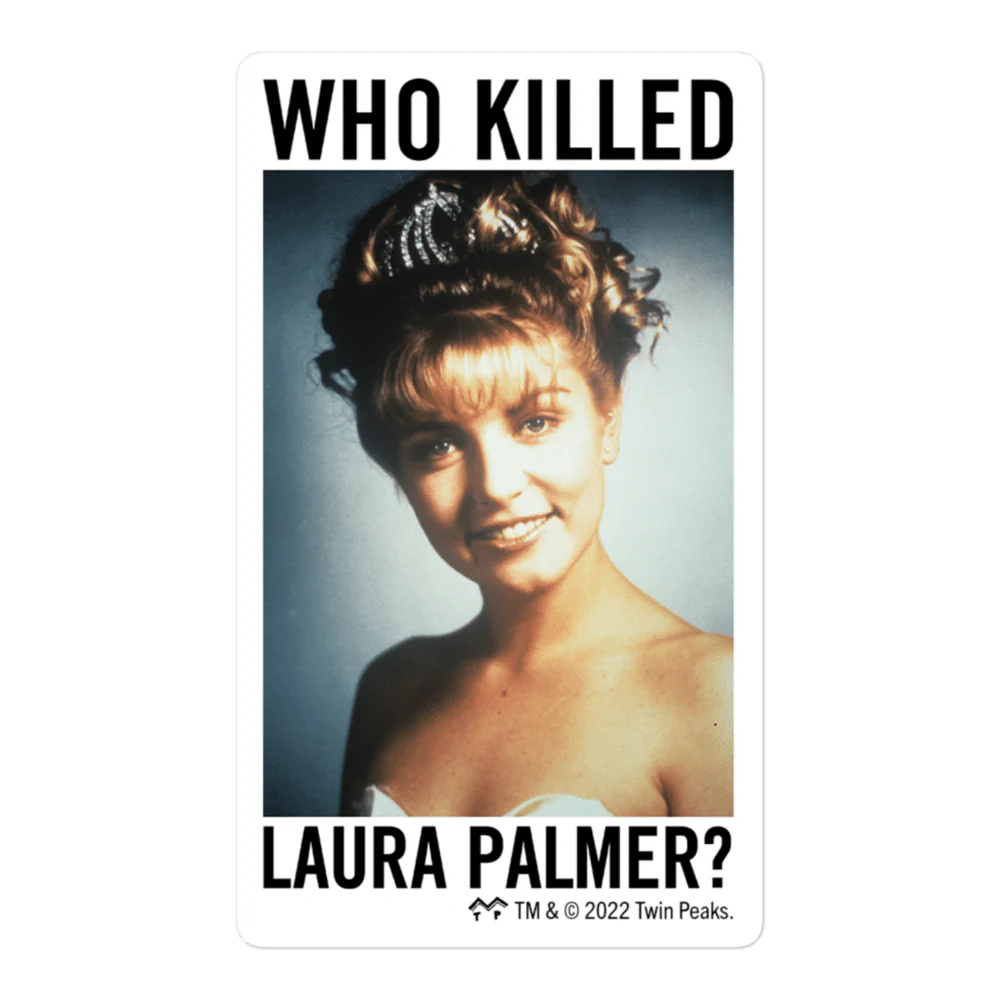

Regarded as one of the most influential filmmakers of the 20th and 21st centuries, David Lynch was famous for exploring reality and our interpretation of it through complex, layered, and non-linear storytelling. Defined most commonly as a surrealist, Lynch’s creativity expanded past an established norm: he took the idea of the conventional and morphed it into his vision. With his unique stories, he played on engrossing the viewer through dream-like visuals yet trapping them within tragic storytelling. Most notably, one of his most famous works, Twin Peaks, is regarded for its amazingly cinematic yet liminal atmosphere. With a persistent layer of fog and thick forests of Douglas firs lining the show’s background, viewers are immediately drawn into the comfy, small-town vibe of the show. But, underneath this appearance hid a complex allegory for abuse and the evil within humanity—a metaphor exemplified by the Palmer family after the murder of their daughter. In another one of his films, Blue Velvet, he painted the scenery of the town of Lumberton, only for the hidden underground life of crime buried beneath its simple appearance to be revealed after an investigation by the protagonist, Jeffrey. Yet, even just describing his work does it so little justice. With supernatural elements, surrealist visuals, and an overarching unexplainable essence, Lynch’s work is truly unique.

Yet, just early this year, on January 16th, after a prolonged struggle with emphysema, David Lynch passed away. Announced by his family in a Facebook post, they remarked, “There’s a big hole in the world now that he’s no longer with us. But, as he would say, ‘Keep your eye on the donut and not on the hole.’” Some of his closest friends, and actors he worked alongside like Kyle MacLachlan and Laura Dern, came out to speak on his death, recalling their years working together and the joy he brought to their lives. Both on and off set, Lynch was known for being an incredibly kind and thoughtful person, which is also reflected through the inclusion within his actual work. Just after his death, in an Opinion Guest Essay in the New York Times, Kyle MacLachlan explained the process of working with Lynch, commenting on his caring and artistic nature. MacLachlan explained, “With his actors, he didn’t want to give straight direction because he saw us as artists and he knew the process of getting there was part and parcel of the art. With his audience, he was the same way. He valued you, as a unique individual, to make of it what you wished.”

Lynch once remarked, “Cinema is a language. It can say things—big, abstract things. And I love that about it.” Cinema, to him, was universal and an immensely important manner of communication, and that showed through his work. His commitment to his art was extensive. In each and every piece he made, there’s a level of control and precision that sets him unique from other filmmakers. Each scene, every character, and every line contributed to building the complex metaphors and themes ingrained into his work.

While often not decipherable to most due to his eccentric, puzzle-like storytelling, his intention and thought still spoke through. He communicated through his film; they speak to not just his life, but the lives of so many. That was his purpose in creating art, to connect to people, to make an impression on them, and to inspire creativity, forever.

Other notable films include: Eraserhead, Mulholland Drive, Wild at Heart, Lost Highway, The Straight Story, and The Elephant Man